it was (not) my fault

[TRIGGER WARNER: For discussion of sexual assault]

This year I accomplished almost all the goals I had set for this decade of my life. I landed a tenure track job at university, I was actively engaged in social justice issues, I was finally financially independent. And sure, it came with some discomfort—I had to leave my friends, my activist campaign, and year-round good weather in a sunny southern California metropolis behind to move to a new, small Midwestern town. But these were sacrifices I always expected to make—I knew there weren’t enough jobs doing what I loved to have the flexibility to choose where I would live. For the most part I had everything I had spent my 20’s working toward.

Here I was, ready for a running start in this new life, and then everything unraveled. It took one bad night and I was reminded how unsafe it is to be a woman and how, as a woman, no matter how hard you work, how much control you think you have, you can never have control. There can always be one night, one man, one incident, which can strip you of who you thought you were. And that is what happened to me.

Below I will tell you my story, but more importantly I want to discuss the themes that surround this story. I hope by articulating them someone else might learn or grow or find solidarity in the experience. I post my story with some reservation. It is long and is not the most important part of this post. I also fear telling my own story will be individualizing what is actually a systemic issue, when so many systemic issues and violences get swept under the rug by positioning them as individual stories alone. But I know context is important, and I know it is important to tell these stories and let the world know they exist. So if you choose to skip my story please do, just scroll through to the next section. If you would like the context of my personal story please continue reading from here.

one bad night

The day the movers delivered all my belongings to my new house, I went out with a colleague to listen to a band at a bar. I stayed after she left to hear the end of the set and that is when the memories stop. Did I drink too much? I had never blacked out before so that seemed improbable, but after some research I learned that in new stressful situations a person can black out even with very little alcohol. Was I drugged? That seemed possible, but I was not unwillingly dragged home by anyone, or dysfunctionally sick the next day. I don’t know how it happened, I just know that about 15 hours of my life were essentially missing to me.

I had flashes of moments that occurred that night, which feel more like flickers of a TV show than they do a memory. I remember talking to a group of people about politics in Israel, I remember one moment of a man helping me walk because I could not quite stand, I remember feeding my rabbits, I remember telling that man I did not want to have sex and him saying okay, I remember making out with that man and being okay with it, I remember telling that man he was getting too close to me and reminding him I did not want to have sex. And that is all. These were the flickers; all strung together it was about one minute recovered from hours of my life. I just had these few flickers and lots of questions. What did he do when I said he was getting too close? Who was he? Why did I not have any memories?

Days later I found the man (or actually, he found me when he stopped by my house to ask me on a date). He stated that we did not have intercourse, he apologized that he did not realize how messed up I was, and even though he swore we didn’t have sex he still agreed to get an HIV test to calm my nerves. Later, a specialist with these cases told me his behavior indicated even if I was drugged, it was not by this guy—that his behavior did not fit the profile.

But at first I did not know any of this. I just woke up with a lot of questions and a lot of confusion so I called a friend and tried to laugh it all off—to call it a hook up. But I could not stick with that story because that is not what it was. I called another friend to ask for help. She admonished me for my bad behavior but she also let me know I could get tests to determine traces of semen and/ or latex. This was great because what I needed most at this moment was to know what happened.

I called Planned Parenthood. They had no openings with a doctor, so they gave me an 800 number that had an automated voice message instruct me to enter my zip code; then they gave me another number to call. I called that number and left a message and a woman called me back. She called the hospital for me and they told me to come in to the emergency room at 4pm (5 hours later) for a SART (Sexual Assault Response Team) exam. So I came in then. I waited in a hospital room for over an hour, close to two, and then it started. They took blood to test for drugs, they preformed an exam to look for tearing (they found none), took swabs to test for semen and latex, and they gave me almost every drug available to prevent or treat almost any known treatable or preventable STI and pregnancy. They didn’t warn me of it, but for a week following this all these drugs left me nearly bedridden as my body struggled to process them.

Then they asked me if I also wanted preventative antiviral medication—drugs to prevent transmission of HIV. The catch? The drugs are very toxic, difficult to be on, and I would be on them for a month. I told them I would take them if they found any evidence of drugs in my blood or latex or semen inside of me.

The other catch? They now told me they would not release that information to me unless I pressed charged against someone.

Now it was about 8pm on a Friday night in a small town where there would at this time be no other doctors available for an exam. I had no desire to press charges—I did not know what happened, I did not know who was with me the night before, and I did not want the state or police involved in my life. So here I was, poked, prodded, examined; all the answers I wanted were in one test tube and on three swabs packed away in a cardboard box sealed with a red sticker that read “EVIDENCE” and I could not access them. They were property of the state.

I decided to take the preventative antiviral medication. I continued to stay on it even after I found the man who confirmed we did not “have sex” and he did not have HIV because, as the infectious disease specialist stressed, I could not actually know what happened, date rape is a very big problem in this community, and HIV does not always show up on tests in the first three months of infection. Plus, this guy could not be that great if he knew I could not stand without his assistance and he still tried to hook up with me—how could I really trust his story? I also decided to take them because every time I tried to stop taking them I got something amounting to an anxiety attack. I would obsessively research HIV and crumble into a dysfunctional mess leading up to the time I had to take the medicine and an even more dysfunctional mess if I did not take them on time. The four weeks before my new job started, when I should have been preparing to teach three classes I had never taught before, editing the journal that needed to go out the door, unpacking my apartment, I was sick. I could not get out of bed easily but I could not sleep well either. The few clear hours a day I had were spent researching issues relating to risk of STI transmission, visiting a therapist and dragging myself to meetings at work. I had reduced control of my body and appetite—I had to force myself to eat meals so I could take the medicine, struggle not to throw up the pills after I took them, and I shit myself twice.

embodying sexism.

A story that begins the way mine does could have been much worse in many ways. And the fact that I am left with a feeling that I am somehow lucky just because this bad situation was not worse, that I somehow feel that this is “not that bad”, is a testament to the problem of sexism and violence toward women in our society. To embody something is to become the physical manifestation of something, to make a concept corporeal. And in the way women come to hate ourselves, blame ourselves, and accuse ourselves when things like this happen, we embody sexism and patriarchy.

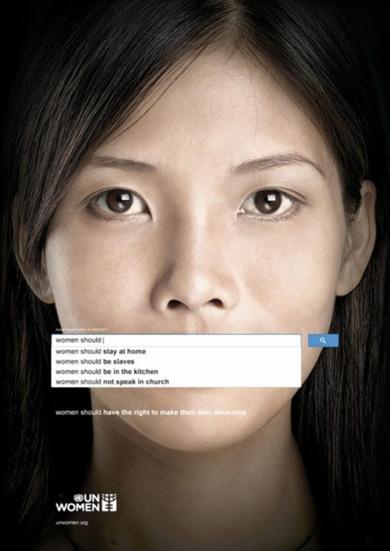

From start to finish, it was all my fault. Or at least that is how I felt and how I was made to feel. And this is exactly how sexism works. Women are to blame—from the moment something happens to her through the way she handles its aftermath. And this will happen every time.

“it’s all her fault-she started it.” Patriarchy allows men to be absolved of all culpability and for women to be blamed. Women’s rapes have been blamed on what they are wearing (tight dresses, and even jeans), acting flirtatiously, drinking alcohol, being out at night, not screaming loudly enough while being attacked, and simply for the fact that they showed up to work. And in many cases, while women take the blame, the men who actually assaulted them have gone free.

I was not raped, but the same blame game was played. I was a woman who drank, and who alone. And if I did in fact black out, who drank too much; or if I was drugged, who did not monitor my drink appropriately. My decisions that night might not have been the safest, but only because of the sexist world I live in that makes the world not safe for women. As my friend Renee articulates:

“[A] woman is not anymore at risk than a man from the alcohol- it is men that put her at risk because of their behaviors.”

However, the man who brought me home that night gets a pass for his decision to engage with a woman who was too inebriated (or drugged) to stand up on her own.

At one point (and it took me a lot to work up to it) I reached out to my ex-partner. I trusted him deeply, and at this point in my life he knew me better than anyone else. He listened to me cry and gave me some consolation, but he also reframed my story:

“It’s not that bad. You got drunk and blacked out and made out with a guy who seems like a great guy. He should get a medal for putting up with you and going to get that HIV test.”

This response forgave the man everything (like taking home a woman who could not stand) and celebrated him simply for not raping me when he had the opportunity. It blamed me for everything at the same time—being drunk, having bad feelings about the events, and advocating for my health by having the man get an STI test.

It was this negative feedback I heard most clearly because it validated the more common and dominant sexist and patriarchal response and it aligned with my own self-hatred. I blamed myself that this happened, and then kept blaming myself for how I handled it.

“it’s all her fault- she is handling it all wrong.” I have spoken before about being sexually assaulted. And somehow, I weathered that storm without all the difficulty that I am having now. Something that looked like an assault did not send me in to the turmoil that this has. And at first this brought me shame and embarrassment. Shame that I did not react “more appropriately” the first time by becoming more upset, and embarrassment that I have reacted so strongly and negatively after this experience.

The man who assaulted me in high school was my boyfriend at the time. After I moved away he began to find ways to contact me and for about a decade he contacted me at least annually, declaring I was his one true love or asking for my forgiveness so he could feel absolved. In my late 20’s I told my then-partner about this and how unsettling it was. I was met with a harsh lecture, loudly in a restaurant, about how I should have reported the assault to authorities and because I didn’t I was likely culpable for assaults of other women. This time a close friend lectured me about drinking too much and not staying in control.

And the worst part is that often we just blame ourselves. My former partner was not the first to suggest a woman is to blame if her attacker assaults someone else—an idea that has always and still haunts me to the point I still have anger toward my 17-year-old self. And my friend’s admonishment in this instance for my drinking at a bar alone cannot even begin to approach my own self-rapprochement.

But the truth is that women are not to blame and we should have no judgment of our own reactions. No two of us will ever react the same and no one of us will ever react the same two times. We are people with experiences, and histories, and other stressors and factors in our lives. We are fluid and as women we are forced to respond and react to a violent, sexist system on a regular basis; our responses reflect an accumulation of those experiences that may at times build resilience, other times denial, still other times exhaustion. Our reactions are genuinely us in that moment and they are not “wrong”.

Part of judging my own reaction was an embodiment of a sexist society that has told me that I am the problem, I am to blame, I am shameful. And as much as I can recognize this I cannot shake it. I cannot stop being angry at my own culpability for the situation, the way I reacted, the way I am continuing to manage the aftermath. And I am so used to the violent way women are treated that I feel guilty writing my story because I have placed my experience on a spectrum of the awful things that happen to women, and know it could have ended up worse. As if somehow that means what happened here was not that bad.

a disembodied self

Unlike embodiment, to be disembodied means to be without or separate from one’s body. I was disembodied through this experience as my body became something foreign and no longer mine.

Most obviously, my body was taken from me for the 15 hours that I cannot remember. More insidiously, my body was policed and controlled by the medical, social service, and policing communities. Because I had this experience and because I accepted the state’s help, I was now responsible to show up when asked and show all when told.

i don’t own myself anymore. The medical interventions I underwent further took my body from me and broke me into my parts, taking my story away from me, and making me measurable and digestible so my experience could fit neatly onto forms—pregnancy results, STI results, consent forms, appointment cards. My body was examined, poked, prodded, and tested. But I did not own those pieces of my body, the only parts of me that could tell the story of what happened to me, the story I so desperately needed to know. The state owned them and I had to collude with the state in order to have that story.

The policing of my body quite literally occurred. Was I drugged? Was I raped? I did not get to know unless I worked with the police and actively pressed charges against someone I did not know for something that might not have happened—which I would not do. I did not get to know unless I agreed that state intervention into my life was a viable, safe and healthy option for me—which I did not think it was.

The SART (Sexual Assault Response Team) program I went through was good in many ways. I had a very respectful nurse and a woman from a local organization offered to meet me at the hospital to advocate for me. (I said no to the advocate I spoke to on the phone, thankfully, because I later recognized her name when she was a student in one of my classes). The hospital visit was free and my medicine was covered for the first week. After that it was around $400 a week but a hospital representative helped me get signed up for medical assistance to reduce it to $4 a week, which reduced my overall medical costs stemming from this experience significantly. But in the end, what I was left with from this process was the experience of my body and my life being aggressively medicalized, policed, and taken from me.

After my initial exam I was told to go to an infectious disease specialist. Once there I was warned that now that I was in this process and there were formal records of it, that I must tell all partners for the next six months of my life about this incident (otherwise I could be charged with willful negligence should they get an STI even though I was testing negative for having any). I demanded more accurate and expensive HIV tests than are normally administered, which are accurate at three weeks instead of three months, so that this could all just be over sooner. I received negative STI results, but they still made me come in three months later for testing, noting legal issues if I did not. (I was later told without apology they misspoke about the legal aspect of it, that they had simply not reviewed my case when they said that.) My anxiety over whether to take preventative antiviral medication was pathologized as anxiety but when I conceded to the medical staff that I get off of the preventative antiviral drugs that were making me sick, the doctor suggested I play it safe and stay on them. There was really no winning and nothing I was being told made sense.

At moments I had agency and felt in control, but mostly I just felt controlled. Just as women on billboards and in magazines become pieces of themselves, just symbols of what they represent (sex, props and products), I became symbols of what was happening to me and was no longer a whole person. I was reduced to my vagina, cells on a swab, tubes of blood, an anxious brain. I was just pieces of a person being monitored and moderated.

That there was such an extreme and humiliating response to something that was being (wrongly) framed by so many as “not really a problem” since I wasn’t “really” assaulted, increased my humiliation and disgust toward myself. It sent my whole self into a pit of shame while pieces of my body turned up for appointments, went into evidence lockers, and filled up test tubes.

medicalizion as a tool of oppression. I did not know what happened to me and I took what I thought to be proactive and responsible steps in the aftermath to protect my health. But the way my body was treated and the way my whole self was disregarded actually created a new form of victimization. Nowhere in this process was I allowed to truly advocate for myself or to be empowered. In fact, nowhere in this process did I, as a whole person, matter at all.

The disembodiment and medicalization of disadvantaged people as a way of revoking their power has always been a tool of oppression. In the 18th century Phrenology became a foundation to justify racial violence and exclusion. Saartjie Baartman, the Hottentot Venus, was a racialized curiosity in the 19th century on display for her buttocks and genitals. Female genital mutilation takes pieces of women away from them, in order to try to control them, just as the tradition of foot binding did. Tyra Hunter was left to die by EMS responders at an accident site because she was transgender—her body parts did not match her gender so her entire person was refused medical care. Jews in the holocaust had their bodies used for medical research; black men in Alabama and Guatemalans were used for US syphilis experiments in the early 20th century; and currently billions of nonhuman animals and their body parts are used for experiments. And the list goes on and on and on.

Separating the body from the individual is a symptom and a tool of oppression. That it happens to women who have been assaulted is just another artifact of patriarchy.

support

Almost as soon as this all happened, I asked for support. I had one friend in this new place I was living. She was 70 miles away but came and helped me. For two days she listened to me, talked to me, sat quietly with me, helped me start unpacking, spent hours with me trying to figure out who I was with and what had happened that night, and slept in the bed with me to help me sleep. When she had to leave she told me directly I needed to keep seeking support.

So I asked others for help too. I asked a new friend closer by to listen to my story and she came through. Holding my secret, checking in on me, making sure I was getting through the medicine okay, letting me talk through my feelings.

And my father, a 79-year-old man who I worried could not really relate, became my rock. He advocated for me, used his medical experience to get me the treatments I wanted when he could, sat on the phone as I read through journal articles. He let me be angry or sad or scared or embarrassed—whatever it was I wanted to feel. He let me talk openly about my sex life and this part of my life that others were calling my sex life but to me felt like anything but that. This was one of the first things that I felt I could not tell my mother out of embarrassment (until now if she is reading), but I knew if I did she would be there for me too.

Asking for support empowered me to tell my story to a few people and that support further empowered me to begin to heal. I encourage people who can to always ask for help. But I also know that my ability to ask for help is a privilege. I am an adult who lives alone and supports myself. I am white and middle class and have a stable job and no one depends on me and I don’t depend on the state system or anyone else involved in this situation in my daily life. Speaking out will have no repercussions for me as it does for so many others. I have privilege that most people, particularly women, do not have.

moving forward

I am writing this blog post because four months after this event I still cannot focus and some days, like today, I cannot do the work that I need to get to done. I freeze up and am triggered every time I see the man that took me home that night. (An all too common occurrence in my new small town). I am writing this post to help myself externalize this and make it real in the world. But mostly I am writing this because even though I have an extreme amount of privilege in this world—including the language to discuss what happened, the resources to pay all the medical bills that came from this incident, the social justice background that allows me to know how to advocate for myself, and the social ties to get support and start to heal—I am still unraveled and unhinged by what happened.

I tell my story as a way to join a chorus of voices who have outted themselves as having had these experiences that are never identical and always not completely describable. These stories many of us feel guilty about because we feel maybe part of it was our “fault” or maybe we shouldn’t lay claim to our pain because other women “have it worse”. I am writing this with the hope that in the cacophony of our voices something will happen and we will finally really be heard. We are being oppressed, raped, assaulted, drugged, abused, and more. And no matter what happens—whether it looks clearly like violence or lurks in more ambiguous corners as my story does—we are being shamed and blamed.

Earlier I said that our society makes it unsafe to be a woman. But it is not just women—it is feminine men, trans* people, people who are not able bodied, people who are not heterosexual, people who are other than white, and nonhuman animals. It is downright dangerous to be anyone who can be othered in this society—more dangerous for some then others but dangerous for everyone all the same. And the systems that are there to protect or serve the vulnerable do not do this in a way that we would want.

My story is just one of these stories that happens a million times a day. And it continues because we have institutions and language built up to that allow for these realities to be sugarcoated in the euphemisms of procedures and forms and programs and guidelines and a quick shove under the rug. These things bolster a framework that blames us for these problems when they happen to us and label us fanatics when we speak out about them on behalf of others. These systems never point at themselves, at patriarchy, at the overarching matrix of domination that makes this world unsafe for more than half of us and oppresses most of us.

It was not your fault.

Excellent post. Thank you for adding your considerable voice to the chorus! We miss it here!

This post is so deep and heavy on so many levels, Carol. I can imagine what it took for you to have written about your personal account in such a public way. Thank you for sharing and for shedding light on the painful realities of rape culture in doing that. I am so sorry for what you were put through. And yes– in NO way was this your fault. And to all other women who have gone through anything similar–it is NOT your fault.

I was raped this year and although I have the social justice background to know that it’s not my fault, I still can’t shake the feeling that it is. This helped me a lot and my day is feeling a little less shitty now. Thank you.

Survivors often struggle with notions of being “at fault” for their victimization. This type of self assigned blame can be seen even in the very young victims of pedophilia. One way to maybe make some sense of this can be to view that “at fault” feeling as something we’re wired for that…strangely enough…offers some hope that we have some control in situations where there was none.

The terror and disorientation associated with feeling that we have no control over what happens to us is immense and terrifying…it just might be that this feeling of being at fault is a way that we have built into us that serves to counter…albeit inaccurately and inadequately…that profound and near annihilating comprehension that we are totally at the mercy of the world (and the beings in that world) around us. Maybe, in a limited and strange way, it’s a way we try to give ourselves some measure of solace and hope.

Part of the condition of living is dealing with the awareness that we can be overwhelmed and harmed by others…through no fault of our own. The harmers rarely take responsibility for their behaviors, opting instead, to pile on the victims and blame them. Never ever trust justifications from individuals or groups of individuals who articulate “reasons” for unnecessary violence or power trips. It is inevitably self-serving and distorted.

I am sorry for your terror and your pain.

Thank you for this blog post, I learned some important things by reading it.

I second what several other people have said, this event was definitely in no way your fault. I sincerely hope that you’re healing, mentally and physically. The world we’re living in has the deck stacked in mens’ favor and that’s not fair or right.

It’s disturbing that MN State would not share the results without you agreeing to press charges… you must have been so frustrated. Putting myself in that situation I would have felt, “this happened to me, this is about me, I want MY results.” Another example of those in power showing that they’re really in charge. Did the state ever give their reasoning for not openly sharing your information?

Best,

I noticed you are friends with Rod Coronado on facebook. I don’t know if you’re aware but he is actually a rapist. The survivors account can be found online.

It wasn’t Rachel Ziegler’s fault either you stupid ass cunt.